One of the most celebrated milestones for a developing baby is their first word. Many caregivers make a point of remembering what their child’s first word was, usually “ma-ma” or “da-da,” and are excited to help them gradually expand their vocabulary to include more words related to what the child sees in their day-to-day life. It’s an exciting progression from the cooing and babbling they’ve been working on in their first year or so of life. However, even though it may be the first real word they’ve said, they’ve been learning their first language (L1) since birth and maybe even earlier. As babies listen to the language around them, their babblings slowly become restricted to the sounds they hear around them (Coelho, 2016, p. 154) and they also pick up on gestures and facial expressions used. The first words or sounds are positively reinforced by caregivers and, as toddlers continue to expand their language skills, mistakes are seen as a sign of development. Adults have a natural tendency to simplify their sentences and speak more clearly to infants and toddlers because it’s understood that their vocabulary is just beginning to grow and it’s a relatively new skill for them.

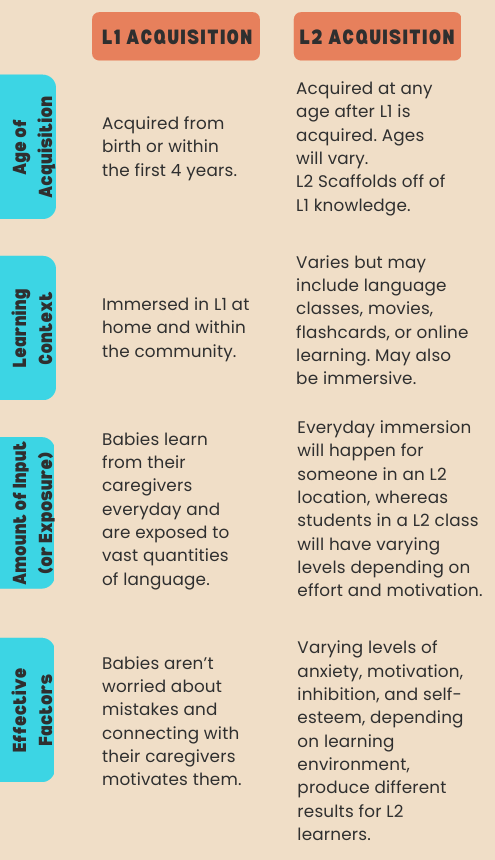

But since you’re a teacher, not an early childhood educator, why does this matter? Let’s consider how this differs from the potential learning environments of someone learning a second language (L2).

There are also similarities between acquiring a first language and a second language:

- Earlier age of acquisition results in higher proficiency.

- Learned patterns may be overgeneralized, such as the -ed suffix for past tense.

- Both processes involve first recognizing the sounds of the language, then the words, and finally the grammar patterns.

- It takes many years to fully learn a language, regardless if it is L1 or L2.

- Involves input, imitation, and habit formation based on the language heard and the praise received.

- Language is an innate cognitive process and learning can happen subconsciously to a degree.

- Social interactions help develop language, especially when they involve modified or comprehensible input. When the input falls in the learners zone of proximal development, meaning slightly above current understanding, more can be absorbed.

- A silent period occurs if learning is immersive when the learner absorbs the language they hear around them before giving output.

Applying language acquisition as an educator

- L1 is learned effortless. Understanding the conditions this process occurs in means being able to replicate it in the classroom in order to help L2 students.

- Understanding the rate of language development, simplifying language that is too difficult, and linking it to context will help L2 students. Grammar lessons are only suitable if the lesson matches the current language level of the student.

- Reading comprehension is minimally affected by teaching phonics to ELL students. A student may be able to sound out a sentence but have little understanding of the sentence’s meaning. Another student may know a word’s meaning but are unable to sound it out proficiently.

- Babies aren’t overcorrected by adults. Instead, adults usually expand their sentences. Doing this in the classroom will provide encouragement to L2 students while avoiding overcorrecting them.

- While it typically takes ELLs two years to develop everyday English skills, they usually need at least five years to acquire academic language to their grade level.

- The peers of L2 students are like moving targets as their language skills continue to develop. This learning gap won’t close quickly.

- Making an effort to learn some phrases in an ELL student’s L1 demonstrates a positive attitude for taking risks in language learning.

- It’s important to celebrate the L1 of L2 learners. As an educator, encourage rich L2 development at home and don’t prevent L2 learners from speaking their L1. Language is closely tied to culture and identity. Further, discouragement of an ELL student’s L1 prevents them from being proficient in any language.

- English has a variety of dialects, some that have many differences from standard English. These dialects need to be honoured the same way as another language and similar supports may be needed.

References

Coelho, E. (2016). “Chapter 8: Understanding Second Language Acquisition” in Adding English: A Guide to Teaching in Multilingual Classrooms. University of Toronto Press.

CrashCourse. (Dec. 11, 2020). Language Acquisition: Crash Course Linguistics #12. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ccsf0yX7ECg&t=1s&ab_channel=CrashCourse

Mango Languages. (Dec 1, 2021). 4 Key Differences between First and Second Language Learning | Science behind Language Learning. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l5j2XfyCXH4&ab_channel=MangoLanguages

Published:

Last Modified: