Following the acquisition of oral language skills, the next stage of language development is reading. Background knowledge and vocabulary are two pieces of language comprehension, which is required for reading comprehension. The importance of language comprehension for reading comprehension is demonstrated by two different models. These models are the Simple View of Reading and Scarborough’s Reading Rope.

The Simple View of Reading

The Simple View of Reading is a mathematical formula that accounts for reading comprehension. The skill of decoding combines with language comprehension to achieve reading comprehension. With it being a multiplication equation, if language comprehension is low, reading comprehension will be directly impacted regardless of decoding abilities (Farrell, n.d.). Similarily, if a students has strong language comprehension but low decoding skills, reading comprehension will be impacted.

Decoding: The developed ability to read words that are familiar and unfamiliar through sounding out words based on phonics and recognizing known words.

Language Comprehension: The developed ability to understand the meaning of spoken language by applying vocabulary, grammatical, and discourse understanding.

Reading Comprehension: Deriving meaning from print by combining decoding skills and language comprehension.

With reading comprehension being the combination of two seperate skills, if one skill is lower than the other, that skill can be focused on for that student and it will increase their reading comprehension abilities. Rather than teaching reading comprehension as a single skill, decoding and language comprehension should be taught and assessed seperately.

A full explanation of how to use the Simple View of Reading to calculate reading comprehension can be found on The Simple View of Reading by Reading Rockets.

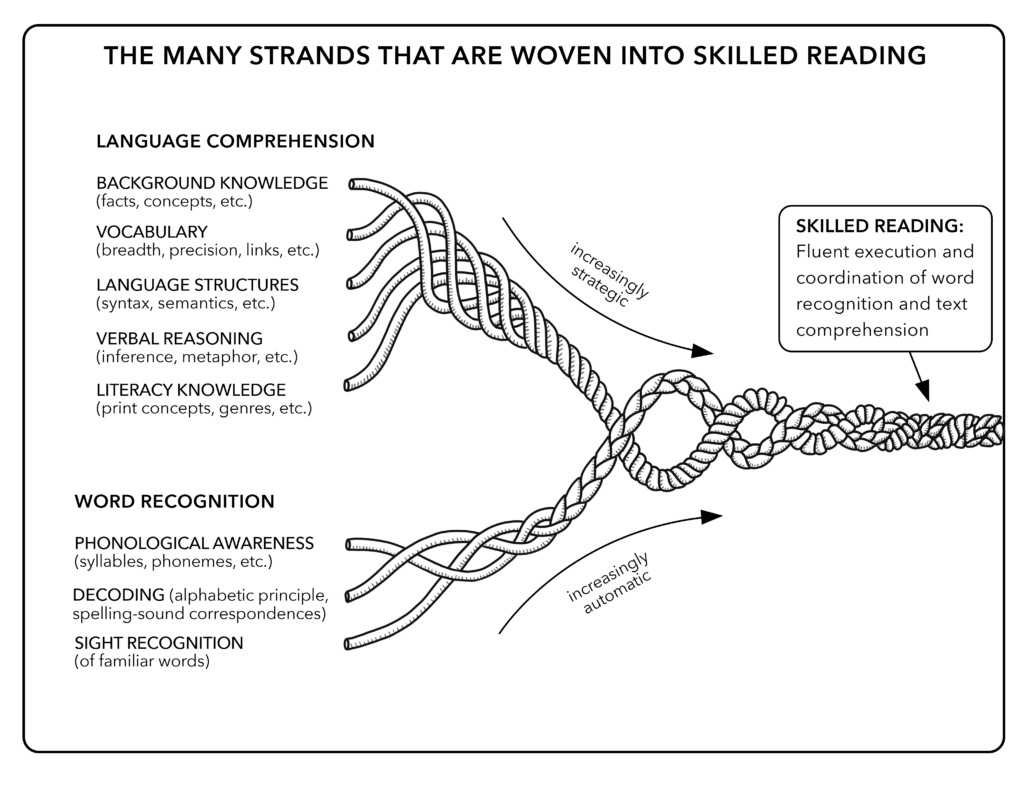

Scarborough’s Reading Rope

Scarborough’s Reading Rope shows how Language Comprehension and Word Recognition are two strands that combine for Skilled Reading. The two strands are each made of different components that can be individually taught in order to develop reading comprehension Developmental Spelling Stages. This model was developed by Dr. Hollis Scarborough in the early 90s but it wasn’t published until 2001. The goal was to inform parents of the necessary skills for reading.

Upper Strands: Language Comprehension

Background Knowledge: Relied on for making sense of what is being read, especially as vocabulary is developing.

Vocabulary: A rich oral vocabulary will make it easier for students to read words they haven’t seen in print before and result in more effortless reading.

Language Structures: Understanding syntax (sentence and phrase arrangements) and semantics (meanings of words and phrases) are essential for reading.

Verbal Reasoning: Drawing conclusions through inferencing and understanding metaphors increasing comprehension of texts.

Literacy Knowledge: Involves knowing genres and layouts of print and literature.

Lower Strands: Word Recognition

Phonological Awareness: The ability to identify the parts of sounds, including words, syllables, onsets, and rimes.

Decoding: The understanding of the relationships between sounds and letters and applying them to pronounce written words.

Sight Recognition: As students practice reading, they develop a lexicon, or mental dictionary, of words they recognize upon sight rather than needing to sound them out each time they are read.

Like the Simple View of Reading, Scarborough’s Reading Rope shows how reading intertwines the two separate skills of language comprehension and the ability to read printed words. Although these two theories were developed independent from each other, they both support instruction of language and decoding as two individual skills rather than only targeting reading comprehension.

Both models emphasis the importance of language skills in order to be a skilled reader. When reading is broken down into the components supported by these models, it means instruction can focus on the weaknesses the students have that are affecting their reading comprehension rather than wasting time reteaching parts they already know.

Phases of Reading Development

Linnea C. Ehri and her colleagues developed a four-phase theory of word-reading development. As children learn to read, they progress through these four phases to become a skilled reader.

Pre-Alphabetic

The first phase is pre-alphabetic. In this phase, readers use “visually salient cues and context cues but not letter-sound cues to read and write words” (Ehri, 2020, p. S50).

Partial Alphabetic Phase

When readers can use knowledge of letter names and sounds to read and write but are unable to decode unfamiliar words, they have reached the partial alphabetic phase (Ehri, 2020, p. S50).

Full Alphabetic Phase

This phase is when readers have learned decoding skills and can use grapheme-phoneme connections. They can read and spell from memory in this phase. (Ehri, 2020, p. S50)

Consolidated Alphabetic Phase

In this phase, readers have an accumulation of word spellings in their lexicon. They know spelling patterns and how they represent syllable and morphemes. The consolidated alphabetic phase is when readers are skilled and have the ability to read longer texts with full comprehension. (Ehri, 2020, p. S50)

Language-Rich Environments

Language-rich environments can help develop language comprehension. By using vocabulary and syntax that is slightly above a student’s level, students can learn new words through context used. When students socialize with other students that have slightly more developed language skills, they can experience a language-rich environment through their peers.

This is also why reading aloud to students is beneficial for them.

“Particularly for struggling readers, teacher read alouds that consist of sophisticated vocabulary and complex language can serve as a scaffold that bridges the gap between children’s current linguistic abilities and what reading tasks require.”

Gámez, 2020, 374

How can this information help English Language Learners?

Language comprehension and decoding have to be developed before reading comprehension can be achieved. Since the vocabulary of an ELL student will be limited, working on language comprehension is important but decoding still needs to be taught. However, if the meanings of words aren’t understood, reading won’t make any sense no matter how strong a student’s decoding skills are.

Oral language development in a language-rich environment will positively impact reading abilities. This includes use of the student’s first language (L1) at home. This will further develop an ELL student’s ability to think deeply in a language they excel in.

Familiarize yourself with the crosslinguistic differences that can help explain students’ mistakes and provide language patterns to scaffold off of.

Ready to learn more?

Check out these great resources:

References

Can Scarborough’s Reading Rope Transform the Approach to Literacy Instruction? Really Great Reading. (n.d.). https://www.realygreatreading.com/blog/scarboroughs-reading-rope

Ehri, Linnea C. (2020). “The Science of Learning to Read Words: A Case for Systematic Phonics Instruction.” In Reading Research Quarterly, 55(S1). International Literacy Association. Pp. S45-S60.

Farrell, L., & et al. (n.d.). The Simple View of Reading. Reading Rockets. https://www.readingrockets.org/topics/about-reading/articles/simple-view-reading

Gámez, P. B. (2020). “High-Quality Language Environments Promote Reading Development in Young Children and Older Learners.” In Handbook of Reading Research, 1st ed. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315676302.

Moats, Louisa Cook. (2020). Speech to Print: Language Essentials for Teachers. Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co.

Science of Reading: The Podcast. (2021, January 13). S3-01. Deconstructing the Rope: An Introduction with Dr. Jane Oakhill. Apple Podcasts. https://podcasts.apple.com/au/podcast/s3-01deconstructing-the-rope-an-introduction-with/id1483513974?i=1000505266955

Wong Filmore, Lily, and Catherine E. Snow. 2018. “What Teachers Need to Know About Language.” In What Teachers Need to Know About Language, 2nd ed., pp 26–43. Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781788920193

Published:

Last Modified: